In this edition of the Lincoln County Gardner, host Ross McCann talks with Master Gardener Joan Crall, Co-Lead at the OSU Demonstration Garden in South Beach. You'll learn about the garden, its exhibits and the many events to be held in 2026.

In this edition of the Lincoln County Gardner, host Ross McCann talks with Master Gardener Joan Crall, Co-Lead at the OSU Demonstration Garden in South Beach. You'll learn about the garden, its exhibits and the many events to be held in 2026.

In this edition of the Lincoln County Gardner, guest host Larry King talks with Master Gardeners Kathy Burke and Terry DeJongh about a series of classes the the Lincoln County Master Gardeners are presenting to help everyone grow vegetables at home..

In this edition of the Lincoln County Gardner, Ross McCann talks with Master Gardener Larry King about rock gardens. Learn about the many types of rock gardens and the basics of construction and plant selection.

In this edition of the Lincoln County Gardner, guest host Larry King talks with Master Gardener Tom Green about how he uses his new greenhouse. They share tips and tricks for growing vegetables in the greenhouse environment.

In this edition of the Lincoln County Gardner, guest host Larry King talks with Master Gardener Tom Green about building a greenhouse to extend the growing season here in Lincoln County.

In this edition of the Lincoln County Gardner, guest host Larry King talks with Master Gardener Ross McCann about seasonal houseplant maintenance. Ross shares the best time of year and techniques for repotting, pruning and fertilizing as well as tips for watering.

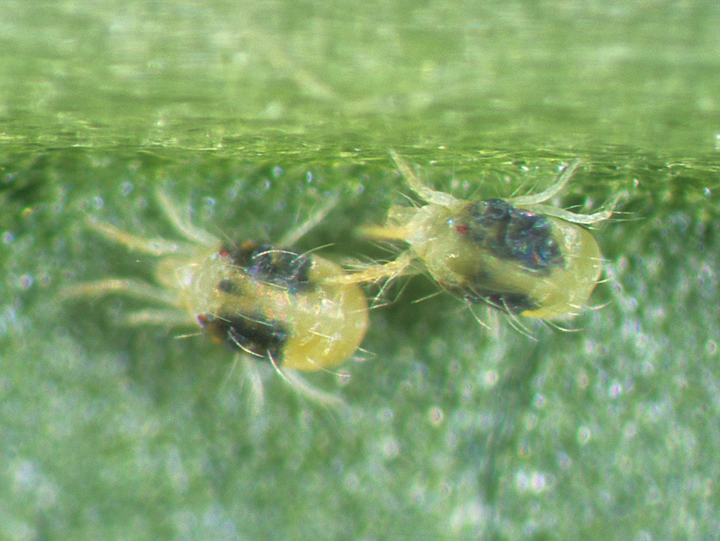

In this edition of the Lincoln County Gardner, guest host Larry King talks with Master Gardener Ross McCann about common houseplant pests. Ross shares his personal experience in identifying houseplant pests and how to manage them.

In this edition of the Lincoln County Gardner, host Ross Mathews talks with Master Gardener Marlene Shapiro about African violets (Streptocarpus ionanthus). African violets are some of the longest blooming of houseplants. Once you know what they like, they are easy to grow.

In this edition of the Lincoln County Gardner, guest host Larry King talks with Master Gardener Ross McCann about pets and houseplants. This is especially helpful during the holiday season, as we often bring extra plants and greens into the home—unaware of their toxicity. Ross mentions the ASPCA research into pet-poisonous plants. Here's a link to their site where you can look up specific plants and pets that do not mix.

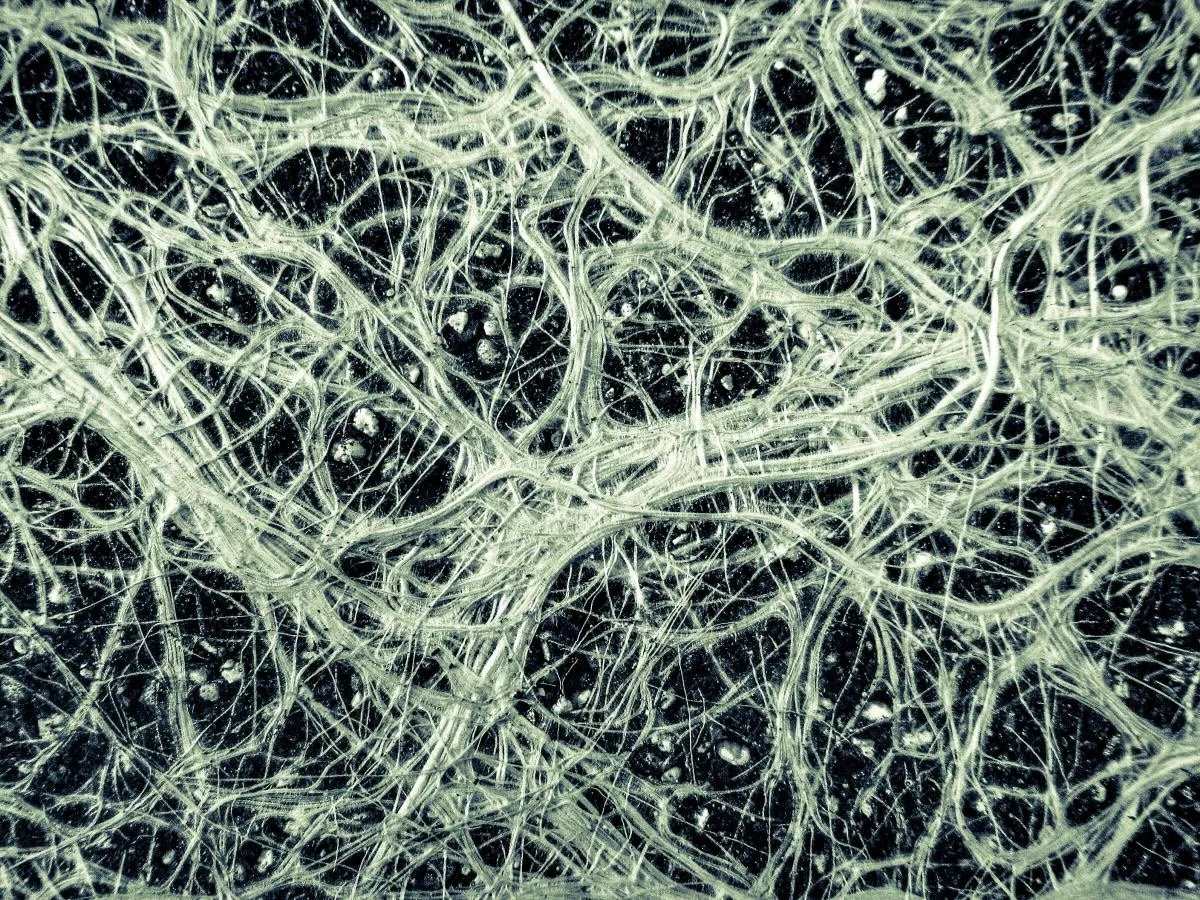

In this edition of the Lincoln County Gardner, Ross McCann talks with Master Gardener Herb Fredricksen about fungi and their part in creating Mycorrhizal Networks. You'll even get a history lesson on how fungi and plants evolved.